Investing in New Teacher Orientation and Mentoring Can Produce Long-term Benefits

The first year of teaching is an uphill climb. As new teachers learn the ropes, they also need to connect with colleagues and adapt to the culture of a new school, and some must also quickly learn content that was not covered in their preparation program. If all that weren't enough, new teachers face the reality of regular evaluations, which for many is their first experience receiving critical feedback as a professional (see here and here). It can be a stressful year.

For the reasons above and the simple fact that individuals in almost every profession—plumbers to professional athletes—get better with experience, there's no shortage of research indicating that teachers improve significantly in their early years. For districts, this often means that retaining teachers is critical to improving teacher quality. Giving teachers a strong start through mentoring and induction programs has been identified as a successful approach to keep more novice teachers in the profession, and, when done well, early career mentoring can help new teachers become more effective.1

In this District Trendline, we explore the mentoring and induction-related policies of 148 of the largest school districts in the United States,2 focusing on new teacher orientation, the duration of mentorship programs, and the additional pay that mentor teachers receive.

Setting expectations

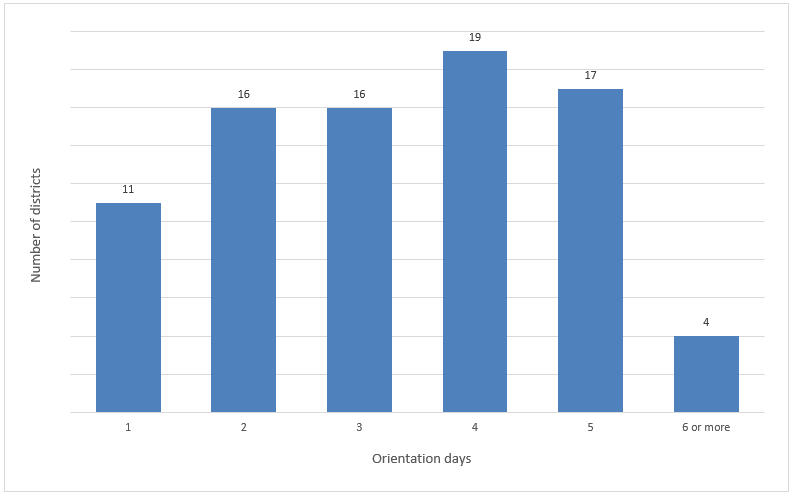

Among the districts in NCTQ's Teacher Contract Database, the majority provide new hires with an orientation to district policy and professional expectations before entering the classroom, but there's little consistency in how many days are dedicated to these sessions, with the range spanning from just one day to as many as nine. Additionally, 56 districts don't address new teacher orientation at all in the materials NCTQ reviews.

Figure 1. Number of new teacher orientation days by district (n=83 districts)

Note: Nine districts in the TCD sample specify the requirement of an orientation, but not the duration. Another 56 districts do not address new teacher orientation in the scope of documents NCTQ reviews.

Some notable districts include Hillsborough County Public Schools (FL), which requires newly hired teachers to complete a training series, including a one-day welcome event; five days of grade-specific content training; and three pedagogy courses focusing on classroom management, classroom culture, and instructional best practices. In contrast, the contract for Sacramento City Unified School District (CA) specifies that new teachers shall have no more than one additional day of service for district-wide meetings beyond what's required for all teachers. Then there's Los Angeles Unified School District, which, in response to a growing trend of teachers entering the classroom with scant preparation, requires a two-day orientation for teachers holding emergency permits.

There is no meaningful research on what should be covered during orientation, or even on how many days should be dedicated to the experience, but with first-year teachers commonly expressing feelings of isolation,3 a poor understanding of expectations,4 and stress related to a workload beyond what they were prepared to handle,5 a high-quality orientation that addresses these concerns is an opportunity to set realistic expectations and provide guidance on where to find support throughout their first years on the job.

Providing guidance

The research is far more clear when it comes to the importance of mentors, and it starts before teachers are even hired. As we've previously covered, several studies have examined the characteristics of pre-service mentor teachers whose student teachers are most successful in their first teaching year. The topline finding was that mentor teachers should be effective instructors, as measured by their contributions to student learning.6, 7 A placement with an effective mentor teacher has a considerable impact, with researchers estimating that in their first year of teaching, new teachers can be as effective as a typical third-year teacher if they student taught with a mentor who has been identified as highly effective.8

The impact of mentorship is a little different for teachers starting their career, though, perhaps because novice teachers spend much less time with their mentors than student teachers. Qualitative measures, such as a survey of state and national teachers of the year,9 find respondents to rank "received access to a mentor" as the most impactful experience for developing their effectiveness as novice teachers. However, studies find a positive impact on student learning only for teachers who received two years of mentoring (rather than only one year).10, 11

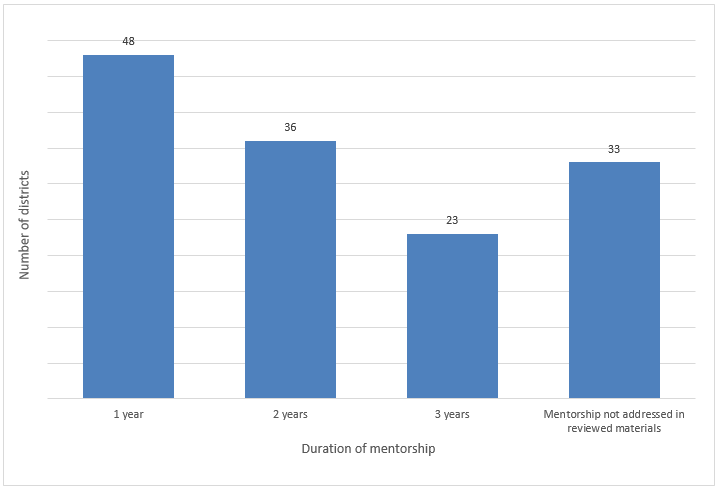

Looking at the 140 districts in our database that either specify a duration or do not address mentorship at all, only 42% of districts require two or more years of mentoring. In other words, the mentorship programs (or lack thereof) in 3 out of 5 districts we've reviewed are likely not enhancing the effectiveness of their new teachers. It's important to note that the selection and evaluation of mentor teachers fall outside the scope of our data collection, so this analysis does not address whether districts consider how effective mentor teachers are, either in supporting student learning or in effectively mentoring new teachers.

Figure 2. Duration of mentorships for new teachers (n=140 districts)

Note: Eight districts in the TCD sample make reference to mentorships, but do not specify a length.

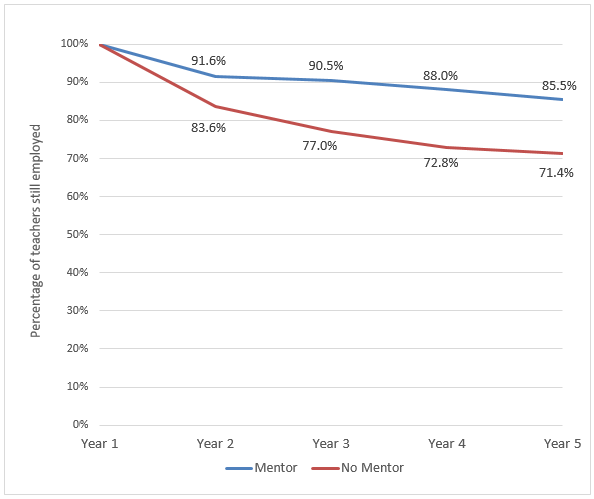

While research suggests that a multiple-year mentorship is more likely to increase teachers' effectiveness, a first year-only program can improve retention. In a longitudinal study on early career teacher attrition, the National Center on Education Statistics found that the number of new teachers still teaching in each successive year was greater among those who were assigned a first-year mentor (see Figure 3).12

Figure 3. Teacher retention increased when first-year teachers assigned a mentor

Source: Public School Teacher Attrition and Mobility in the First Five Years: Results From the First Through Fifth Waves of the 2007–08 Beginning Teacher Longitudinal Study

Compensating mentors

An important consideration with any mentorship program is the responsibility placed on the teachers providing guidance. The additional role/responsibility calls for compensation, which we found in 74 of TCD districts. Where compensation exists, what stands out is the range of stipends that mentor teachers receive:

- Boston Public Schools (MA) extends New Teacher Developers (mentors) an additional 5% above their base salary. As examples, a teacher with a bachelor's degree and five years of experience would receive $4,400, while a teacher with a master's and 10 years of experience would earn $5,500.

- Cherry Creek School District (CO) gives $500 to mentors who have completed the district's course on mentoring and $350 for those who have not completed the course.

- Des Moines Public Schools (IA) offers a $2,500 annual stipend for one mentee and an additional $1,500 for a second mentee.

- Lewisville Independent School District (TX) provides $250 for mentoring one to three new teachers and $500 for mentoring four or more.

- Prince George's County Public Schools (MD) pays $750 per mentored teacher.

While there are many factors and considerations when setting pay for mentor teachers, what may be most important is that the chosen compensation attracts veteran teachers who are both effective instructors and capable mentors.